For those of you who don't know, the history of the game is perhaps just as interesting as its mechanics.

In The Beginning...

You see, in the mid to late 1970's a man by the name of Gary Gygax helped co-create the world's first RPG, Dungeons & Dragons. He helped design the mechanics, write the rulebook, advertise and manage sales. He was the CEO of the company that published the product, TSR.But then something interesting happened in the mid 1980s. Gary Gygax was ousted from his CEO position and forced to leave TSR forever. Here's a man who spent a decade nurturing a product that was near and dear to him, and now it was no longer his. Worse yet, the company he helped found; voted him off the board effectively making TSR a competitor. Mr. Gygax was exiled and forced to say goodbye to D&D for good.

Can you imagine the heart break he must have felt? After pouring your heart and soul into something like that, and now it belonged to someone else.

The Second Age

But, Gygax being a gamer by heart, did what any intrepid adventurer would do. He picked himself up, mended his wounds, and marched on.To me, this is where the story of Gygax gets interesting. People tend to only focus on Gygax's first creation, Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 1st Edition (or derivatives such as Basic Dungeons & Dragons). But what kind of game would the new Gygax 2.0 create? With a new team, and nearly 15 years of experience in the industry, he had the opportunity to start completely anew.

Haunted By The Past

Except, no matter how willing Gygax was to moving on, it seemed the past was not willing to let go of him. TSR, now under new management, was determined to defend their golden goose through copyright protection. Partially because of this, Gygax had to go to great lengths to distance his new game from that of D&D. He came up with new terms (such as "Heroic Personae" instead of "Character") to insure it was a bona-fide standalone game.Yet, alas, Gygax did not prevail. When TSR sued the company that published his new game (Dangerous Journeys), the company eventually gave in and transferred the rights to TSR, where it was promptly mothballed.

Today I want to talk about this hidden gem that was tragically killed off all too soon.

The Game

Game Basics

Under the Dangerous Journeys umbrella was the "Mythus" fantasy roleplaying setting/game. A hybrid fantasy world, mixed with fantasy-specific mechanics.

As someone who cut their teeth on GURPS, to me all of this sounds pretty awesome! A universal system, made by Mr. Gygax? Wow! The man sure had changed since the 1970s.

How Does It Work?

Vocabulary

Well, first off, as I stated earlier; there are a lot of propriety terms. These terms are, in my opinion, un-needed in modern times, and end up detracting from the overall experience due to the confusion they cause to the reader. For example, "Personaes", or "Heroic Personaes" (HP for short) refer to what most players understand as "Characters". The fact that the acronym "HP", which commonly stands for "Hit Points" or "Health Points" is used to describe characters, is in my opinion inappropriate.Other examples include the "Socio-Economic Class" (SEC), TRAITS, Vocation, and, oh yes, the "Knowledge/Skill" (K/S) and STEEP points. It's all very heavy jargon for a game, in my opinion. So, to spare you dear reader from a head ache, I'm going to translate these terms to more acceptable vocabulary.

Character Creation

Enough talk, let's get into creating a character! Character creation is divided into "Basic" and "Advanced" forms. Which is nice if you're a fan of "Basic Dungeons & Dragons" and "Advanced Dungeons & Dragons". Except here the two forms are in one book. Nice!Step 1 involves determining where your character belongs in the world. More specifically, their social class. Are they a peasant? Perhaps a "freeman", or even an aristocrat. You determine this by rolling 1D6+1 (the +1 seem unnecessary. I'm sure there's a more eloquent way to have handled that, but I digress).

Make your roll and refer to the list below:

This step is somewhat important because the level you rolled (see the image above) will determine what type of class you can play later on in the creation process.

Step 2 covers the character's basic attributes, known here at "TRAITS" (with all caps, apparently). This is a percentile-based game where there are only three main stats: Mental, Physical and Spiritual. These traits are filled out by dividing 120 points between the three attributes. You decide how many points each stat has, but no stat can have less than 21 points nor more than 60 (to start).

The game goes on to state that a score of 60 is the human-maximum when it comes to abilities, whereas a 21 is a "very low average".

As with previous Gygax games, it seems Gary wanted your "Heroic Personae" (character) to be somewhat extraordinary; a cut above the crowd. For this reason, the 120 points can be equally divided into three groups of 40 (which is listed as "above average"). The advanced version of the game starts characters with twice as many points (252 pts), reiterating this "super human" focus.

Step 3 Next, we're off to choose our class...sort of. In Mythus classes are called "Vocations" and act more like a bundle of skill-sets that a character specializes in. The basic version of the game offers seven vocations, with the advanced version (found at the back of the book) offering as many as 45. The seven starting classes are: Alchemist, Astrologer, Cavalier, Mercenary/Solider, Mountebank, Thief and Wisewoman/Wiseman.

Clearly Gygax had designed an easy framework by using skill bundles that merely required the re-organization of which skills a class started with, rather than fine-tuning each "vocation" to stand out from the crowd.

The image above showcases the basic classes to choose from, along with what basic attribute they focus on, and the minimum social class you must have rolled during step 1 to be eligible to take this class. For example, a Cavalier requires your character be a "freeman, gentleman" or higher, and will focus mostly on physical skills.

Step 4 Next we'll chose our skills, known in Mythus as "Knowledge/Skill" or "K/S". Mythus makes a distinction between K/S and another term, known as "STEEP", which essentially are "skill points". Skills (e.g. lock pick, sneak, swim, etc.) are given skill points (STEEP) which represent how well your character can perform in a certain field of study. Again, a score of 20 or below is considered poor while a score of 60 or above is impressive.

As I mentioned earlier, classes in Mythus aren't necessarily fine-tuned snowflakes, each with unique characteristics. Instead, they pretty much only represent a bundle of skills. This makes sense for the type of game it is, since Gygax deliberately chose three broad abilities to define a character, and he wanted the game to be both percentile-based and universal.

|

| The "Skill List" |

What we find is that the class has a list of skills (as mentioned before), along with what basic attribute (physical, mental or spiritual) the skills are based off. In the far-right column we also see the starting skill points (STEEP) that the character gets for each skill. These skill points are added to one-half (1/2) of the character's basic attribute. For example, an alchemist with a mental score of 30 would add one-half of that (15) to their mathematics score of 20 (for a total of 35).

Why one-half of the basic score? I have no clue. I suppose Gygax didn't want the numbers to climb to 100 too fast. However, I feel like the same goal could be achieved by simply reducing the number of starting skill points; or starting with less points for the basic attributes.

Additionally, there are three "universal" skills all players get: native tongue, perception and riding.

We're not done with skills just yet. Gygax decided to allow the players to customize their character further by choosing "bonus skills". The way bonus skills work depends on which of your basic attributes (physical, mental, spiritual) has the highest score, which has the lowest and which is in the middle. You choose a number of bonus skills equal to 3, 2 or 1 (for your highest, second-highest and lowest basic attribute, respectively). For example, if your character's spiritual score was the highest of the three, you choose three bonus spiritual skills (e.g. magnetism, metaphysics and street-wise). You'd do the same for your two other basic attributes (with one progressively less skill for each).

You might be asking how many skill points each of these bonus skills starts with, and the answer is 10 points.

Step 5 which is, oddly enough, called "Step 6" in the rulebook (it seems step 5 is missing), involves determining the starting money for your PC. However, it's not a simple matter of rolling 3D6 to determine how many coins are in your pocket. In Mythus, you have "Net Worth", "Bank Accounts", "Cash on Hand" and "Disposable Monthly Income". The currency is called the "Base Unit Coin (BUC)". How's that for generic?

To start, you determine your PC's social economic class (found in step 1) then roll a certain number of dice for each money category (as shown in the table below) based off their social class level:

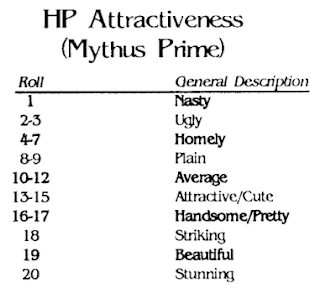

Step 6 The final step involves finding some miscellaneous information about your character. Specifically, their physical attractiveness.

Roll a 1D20 and pray you roll above a 7.

For the basic version of the game, that concludes the character creation process. The rest of the book goes into "performing actions", "heka" (which is their proprietary name for magic/mana), "combat", "leveling up", "how to play your character" (and example play sessions), the advanced version of the game, "game master rules", two sample adventures and "magic items" (along with an appendix). All of these topics I'll have to save for another post.

In Conclusion

Deep down, the mechanics of this game aren't bad. If you're into percentile-based RPGs, there's a good balance between the luck-of-the-draw and customizing your character the way you want.The Good The game had massive potential, on paper. It was a universal system, it used D100 percentile rolls, and the basic version was intentionally left generic. This allowed players (and GMs) to tailor the setting to almost any genre (though the game was flavored towards fantasy). A "wiseman" could become a "jedi" or a "cavalier" could become a Captain America of sorts.

I also liked the tie-ins between a character's starting social status and the options they had available later in the creation process. Once the system is understood, the mechanics are fairly easy to follow and transparent in intention.

The Bad At times the game feels too generic. The BUC is a good example of where one-size-fits-all doesn't always "feel" right in certain settings. Species apparently aren't an option to choose between during character creation. There also wasn't enough differentiation between the classes (but this is more of a gripe I have towards skill-based systems as a whole).

The skills also felt a little confusing (e.g. "Phaeree Folk & Culture", "Apotropaism"). They also came off as a tad bit random since some seemed far more useful in a day-to-day play session than others (e.g. "combat, missile" will always be better than "agriculture").

Instead, I think Gygax should have let players make up their own skills, and assign them to the most logical basic attributes with a generic number of starting skill points.

The Ugly Obviously the TSR lawsuit sunk this ship; but even if TSR allowed the game to publish and thrive, there were still some major rough edges that needed grinding down. To start, the cryptic nomenclature is almost laughable. Referring to things as "K/S", "STEEP", "Heroic Persona" and "SEC" isn't my idea of a fun Friday night. While I appreciate the great lengths Gygax went to to avoid a lawsuit (which ultimately happened anyway), the vocabulary needs some major cleaning up. If a "retroclone" of this game ever gets made, it's the first thing that has to go. Use normal, industry standard terms that everyone knows and loves.

Secondly, the wall of text. Each page is jammed packed with small-sized font that talks about every facet of every mechanic (and doesn't always do a great job of it, either). Many concepts and ideas could be explained in far-less verbage, and allow for more white space.